Benefits of Guardians in Alaska Ripple from Bristol Bay and Beyond

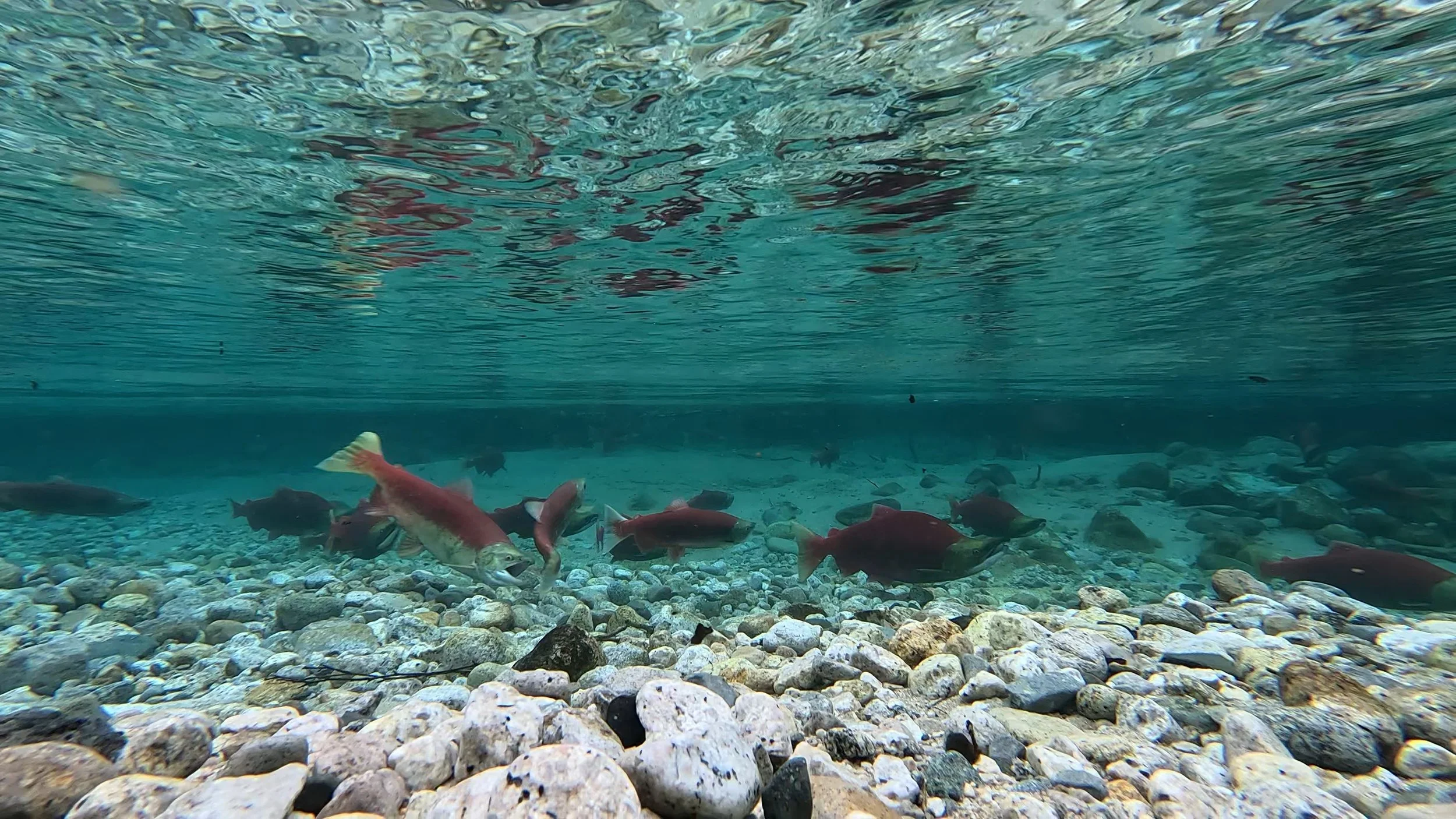

Sockeye salmon in the Knutsen River.

All photos courtesy of Bill Kane, Tribal Steward.

December 1, 2025

It’s a cool and crisp morning on the shores of Lake Iliamna, a region with less than a thousand people, in Southwest Alaska, as Mary Hostetter, a Land Guardian, and Brandon Jensen, a drone pilot working with the Bristol Bay Guardians initiative, prepare for a drone flight. Mary and Brandon are in Pedro Bay and will drive from Brandon’s home to Knutsen Beach to survey spawning salmon with their research partner, Curry Cunningham. The project is supported by the Bristol Bay Guardians – an initiative in Alaska expanding environmental stewardship in the Lake Iliamna region – which captures aerial drone footage of adult Sockeye salmon returning to spawning grounds in the Kvichak watershed. The project is creating a baseline understanding of sockeye salmon spawning data by collecting drone imagery from streams and beaches, and is important because “It’s not only about understanding how many salmon there are, but also understanding their relationship with the rivers and how they engage with the whole river system,” shares Hostetter.

Mary Hostetter and Colter Barnes training to conduct drone surveys of the Gibraltar River.

Here, like many places across Alaska, climate change is already impacting the land and the patterns of wildlife migrations. In turn, this affects the communities that rely on their finned, four-legged, and winged relatives for traditional harvesting. By collecting the data, the Guardians program is filling a gap left by budget cuts from the State of Alaska, which no longer has the funds to maintain a program for aerial surveys of sockeye salmon spawning activity in the Kvichak watershed. “It’s important for communities to understand what level of abundance our salmon are returning in so that we can build on our traditional knowledge and plan for our futures,” continues Hostetter. The project is important for salmon data – but it also highlights another priority within the Bristol Bay Guardians initiative: partnering with and employing local people in sustainable jobs rooted in culture, language, and love of the land.

Practicing drone surveys on the shores of Lake Iliamna with sockeye salmon.

Inspired by thriving Indigenous Guardians programs operating throughout Canada, the Bristol Bay Guardians initiative is centered on the transformative power of Indigenous-led stewardship and collaborative partnerships to enhance community resilience and well-being. The Bristol Bay Guardians is one program of many established and emerging across the state.

Originally, the pilot project for the initiative in Igiugig began in 2022, when they received a grant through the Tribal Stewardship Office for a regional community-based monitoring program, and expanded in 2024 when Igiugig Village and the Nature Conservancy were awarded a $1.9 million (USD) grant from NOAA’s Climate Resilience Regional Challenge program. Three years later, the Bristol Bay Guardians are engaged in a variety of projects: they are partnering with the National Audubon Society to monitor migratory bird populations in vital bird habitat, operating a cooperative agreement with the US Fish and Wildlife Service to expand upon early detection and response to invasive species in the region, engaging in a salmon ‘egg box’ pilot project, creating a collaborative caribou population monitoring agreement in Katmai National Park and Preserve, and developing a regional sockeye salmon monitoring program, just to name a few.

Bringing the Decision-Making Back to Communities

Overlooking Kukaklek Lake, searching for caribou.

In the past, some of these projects may have been overseen by state, federal, or private researchers or scientists, but the Guardians initiative goes beyond employment: it creates jobs for local people that recognize their contributions, and also drives the priorities of the research to fit community needs.

In communities around Lake Iliamna,–like many other Alaska Native villages–Indigenous knowledge is abundant, but has not been historically recognized by outside researchers or decision-makers. Having Guardians on the ground changes that: Guardians are trained experts who use both Indigenous and Western science and inform the decisions that Tribal Nations or communities need to make. In Alaska, that can also inform funding and Tribal engagement with State or Federal entities. “In the past, most Alaska Natives were not involved in science and research. We have hundreds of years of colonizers coming in and telling us that our observations about the land – the way that we moved on, lived within, and thrived in these landscapes – didn’t matter,” shares Hostetter. “A significant amount of research and monitoring in Alaska Native communities is funded through federal grants. But those have always valued the fed’s priorities over the needs of the community, and industrial and extractive industry priorities guided what research happened on the land. But the Guardians program is a pathway to being in charge of that research, of giving the power to the communities to inform decisions.”

Sustainable Jobs in Remote Areas

Jon Salmon on the land looking for moose.

Another positive impact of building a Guardians program is that it also changes people’s perspectives about themselves and the knowledge they hold about the land, water, and wildlife. For the first time, Hostetter says youth are seeing themselves represented in the environmental monitoring jobs, and realizing that they could combine their knowledge of their homelands with a traditional degree and put that to work as a Guardian.

“The option of being a Guardian, of having stable employment in a remote village, could be a game-changer,” shares Hostetter. Like in many places across the North, jobs can be hard to find in remote communities.

Because of the complicated geopolitical land-ownership rights and titles in Alaska, many of the jobs in these remote regions are in extraction, like mining or oil and gas drilling. Many of these industry projects promise jobs, but then rely on outsiders who travel in seasonally to work and leave after a short time.

The Guardians programs not only provide a more sustainable alternative to extractive industry, they also ensure that jobs are provided to local people, and that the gifts, talent, and knowledge are nurtured within the community. This is at the heart of what’s at the Guardians movement: work is rooted in Tribal sovereignty, cultural revitalization, language, and Alaska Native’s way of life.

Filling the Emergency Response Gap

A boat travels on Kaskanak Creek, a tributary into the Kvichak River, an important traditional harvesting area.

Guardians programs also offer a solution to another need growing across Alaska: emergency responders. Remote communities across the state are no strangers to impacts from climate change. In Igiugig, the Guardians program is involved with monitoring climate data related to snow depths, but in 2024, they were only able to collect two data points over the course of eight months due to very limited snowfall–a major departure from the norm. And research suggests that the Arctic, which makes up a large portion of Alaska, is warming at a rate four times faster than the rest of the planet. Here, many communities have been warning of changes for decades. Most recently, remnants from Typhoon Halong devastated communities in the Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta, displacing hundreds of people and rendering entire villages uninhabitable for the foreseeable future.

While the Guardians programs can’t prevent these horrific climate-related incidents from taking place, plenty of examples exist of Guardians serving as community-first responders in emergencies like flooding, boat accidents, and wildfire response. Miaraq Warren Jones, Regional Alaska Coordinator for the Indigenous Leadership Initiative, thinks that Guardians offer a major shift for addressing emergencies and climate impacts in Alaska Native communities–including those that are only accessible by small aircraft or boat.

“Not only is training Guardians a cost-effective strategy for responding to emergencies both small and large,” shared Jones, “it also just makes sense. It takes a long time to get state or federal personnel into these villages. And with the current federal government decreasing budgets across the US, we have a lot fewer people in positions to be engaged in these spaces. We should be building up our community resiliency now, before it’s too late.”

From Local Conversations to AFN: A Growing Guardians Movement in Alaska

Brandon Jensen, Mary Hostetter, and Curry Cunningham sharing knowledge of drone surveys on Knutsen Beach.

Momentum for Guardians is growing across Alaska at both the local and policy levels: many communities already operate their own Guardians programs, and many more are asking how they can establish one. At the 2025 Convention of the Alaska Federation of Natives (AFN), the Aleut Community of St. Paul Island Tribal Government introduced a Resolution to officially recognize Guardians, Rangers, and Sentinels programs as a pathway to strengthening Tribal Sovereignty, food security, and climate resilience.

The Resolution outlines how these programs provide meaningful employment, train the next generation in both Traditional practices and Western science, and strengthen local economies through Indigenous-led stewardship.

Delegates of the 2025 AFN called upon the Alaska Congressional Delegation, the State of Alaska, federal agencies, and philanthropic partners to recognize, support, and secure permanent, recurring investment in Sentinel, Ranger, and Guardian programs, and to incorporate them into Tribal, state, and federal co-management frameworks. They also urged collaboration with Tribes, Tribal organizations, Alaska Native corporations, and other Alaska Native organizations to expand these programs statewide.

As Guardians programs grow across Alaska, they are looking for a framework to establish their initiatives, much like Mary sought when she began establishing the Bristol Bay Guardians initiative. The program, which will become a small regional network and hub for data collection and sharing, is an inspiration to many and a model for how programs can operate in the state.

Hannah Marie Garcia-Ladd, Program Director of the Indigenous Sentinels Network–a well-established Guardians program based in the Aleut Community of St. Paul Island–shared that the work of Sentinels, and the work of Guardians across the state, is unique in the broader political environment of Alaska. She sees the work of the Sentinels in her community in the same way that Hostetter sees the Bristol Bay Guardians: they are taking back their own power as Alaska Natives in decision-making about the resources the land holds, and having the tools and resources to inform the decision-making about how to steward them. Garcia-Ladd shared that, “Guardianship means seeing ourselves in the process of caring for our homes, not just ‘managing’ resources, but truly caring for them.”

USGS stream gauge river assessment.

Back in Pedro Bay, Mary, Brandon, and Curry have finished the flight and are uploading hundreds of drone images, each highlighting a section of Knutsen Beach that contains the spawning sockeye salmon. These images are a growing database of research owned by the community, and can help build resilience and reinforce Tribal sovereignty. “I get emotional because growing up, I never saw people from our communities–anyone who looked like me–doing this work,” shared Hostetter. “Being a Guardian for me is a return to knowing that our lived experiences on the land is real knowledge. The fact that I represent our Alaska Native selves back to ourselves…our youth…it is so powerful.” It’s her hope that every community in Alaska gets a glimpse of that: of what Guardians do, what they can mean for a village, why they should support that vision–and eventually see themselves in it.